Artlink Magazine

1st June 2014

Moments of intersection

James Tylor.

If you spend more than a few hours with Adelaide-based photographer James Tylor, conversation will inevitably turn to culture: its meanings, definitions and the way in which our heritage tends to define our perception of self and others' understanding of us. As a man of Aboriginal, Mãori and British descent, these issues have been central to many of Tylor’s experiences growing up in the Kimberley region of Western Australia and the far west of New South Wales. The points at which these bloodlines intersect lie at the heart of Tylor’s practice as he explores his hybrid identity, attempting to find a balance between these three cultures and both his contemporary experience and personal understandings of them. Tylor joins an increasing number of artists working in this area, such as Julie Gough, Lorraine Connelly-Northey and Jason Wing. Each of these practitioners acknowledges their diverse backgrounds and examines the ways in which their multi-racial heritage affects their individual identity.

Exhibited in his first solo exhibition, at Marshall Arts, Adelaide, in November 2013, Past the Measuring Stick (2012) was a series of small ambrotypes, developed on black glass, each depicting what appears to be a turn of the century Indigenous artefact. The plates could be part of a museum collection; their appearance is suggestive of documentation created by early colonial explorers. These objects and glass plates however are not from another time. Each one is a hybrid work, an Aboriginal tool created using Maõri materials or vice versa, captured with one of the earliest photographic processes, commonly used by British explorers to document their discoveries. From construction to documentation, Tylor has created these objects from both sides of his 'lens’, telling both the Indigenous and colonial stories simultaneously.

The artist aims to find a peaceful balance between these three histories, utilising 18th century tools and processes to re-imagine a moment of their intersection and bring it into a contemporary setting. These photographic plates challenge the lens through which we view museum pieces. If this work, so closely resembling an ‘authentic’ artefact was created by a contemporary artist, what of those ‘timeless’ pieces on show in museums? Are they objects from a dead culture or rather, working tools and artworks of a culture that is living and continuing to this day? And how do we separate the art from the ethnographic object? Whether or not Tylor achieves his goal, these pieces provoke thought and discussion both in the gallery and beyond.

Tylor’s work is not only conceptually challenging but often aesthetically beautiful — a characteristic that works to draw viewers into his complex exploration of culture. His series hopes, dreams and nightmares (2013), consists of exquisite, small daguerreotypes depicting picturesque farmland scenes. Their scale encourages the viewer to lean in close, to see the tiny images of trees standing alone in paddocks, an outcrop of introduced species on a horizon. Each image is created in-situ and developed onto highly polished pieces of silver so that the face of the viewer is reflected back to them. The effect is one in which we become part of the image, implicit in the scene by inclusion of our likeness. But the beauty of these plates is deceiving, the history of these sites only hinted at by their title and, once discovered, the truth is jarring. These are scenes shot around Tylor’s father’s farm in Victoria. As he describes “my father would tell me stories as a child of our old farm, battles between the first European family who farmed there and places that have never been farmed on because of what lay beneath”. Tylor exposes an alternate history of Australia and its colonisation, and through these works acknowledges the fate of his people enacted by the other side of his cultural heritage. Each work is tied intimately to his present through a connection with this land and his childhood.

Voyage of the Waka and, the Origin of the Dreaming (2013) created as part of his postgraduate study, began with extensive research into Charles Darwin and his journal Voyage of the Beagle, written on his second voyage of discovery from 1831-1836. It was at this time that Darwin was developing his theories of evolution, and visited both Australia and New Zealand. On this journey he encountered and documented not only Mãori and Indigenous Australians, but also instances of mixed race relationships. There is another link to be made between these journals and Tylor’s own practice: it was at this time that the daguerreotype was developed and employed to capture these travels. Armed with this knowledge, the artist has re-imagined the journey, producing a series of fractured close-ups; the fierce eyes of a warrior, the palm of a hand bearing the words ‘English Nunga Mãori’, a woman’s chin bearing a Tã Moko, a traditional Maõri face tattoo. Many of these works are self-portraits, Tylor again placing himself on both sides of the camera. These images are representative of the way in which the artist understands his own identity, how these three cultures have merged and interacted, and how this merging can now be represented, using one of the mediums through which Indigenous peoples were originally documented rather than understood.

Much of the strength of Tylor’s work is derived from the way in which he begins with intimate moments, quiet times of reflection and personal stories, and reimagines these experiences. He is then able to tie wider histories into his understanding of his own multi-racial identity. Tylor lives these lives, through research, creating artefacts and taking part in an intimate and tactile photographic process: often, chemicals can still be smelt on his skin after a long day in the darkroom. There is little judgement in these images, they do not harshly accuse but rather offer an invitation to reflect. He understands that to ignore part of his heritage would be at the detriment of those other histories, and would be a betrayal that would leave him understanding only part of who he is. Through a practice that brings these cultures and experiences together, Tylor is able to explore both his own identity and contribute to a contemporary understanding of culture.

Image credits in order of appearance:

James Tylor, Kauri Clap Sticks, 2012, from Past the measuring stick series, ambrotype on black glass with clear glass face mounting. Courtesy and © the artist.

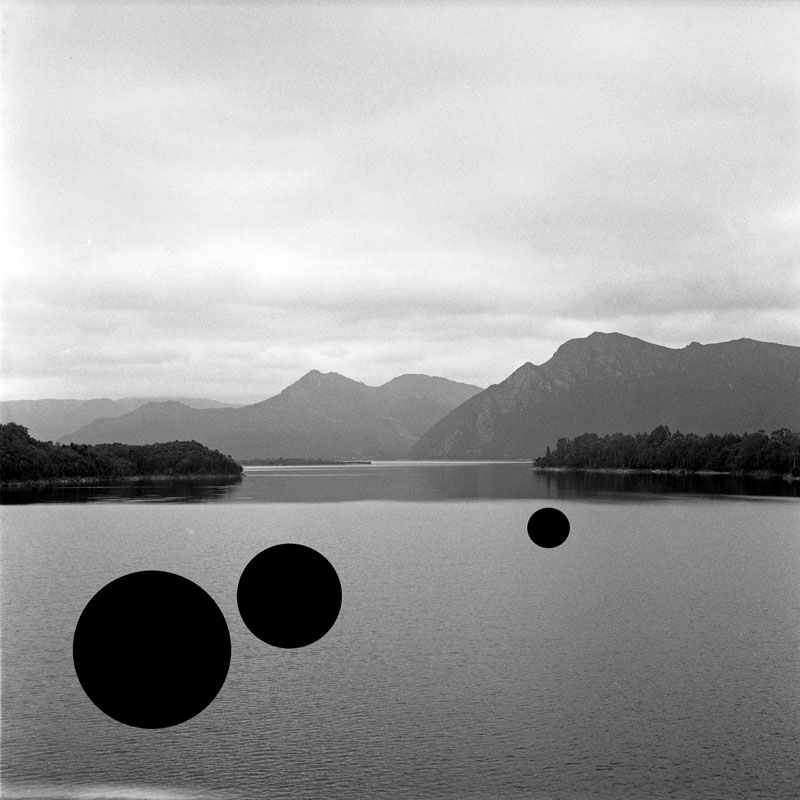

James Tylor, Deleted scenes (from an untouched landscape) #6, 2013, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle paper, velvet. Courtesy and © the artist.

This feature article published in Artlink Magazine 1st of June 2014.

James Tylor, Kauri Clap Sticks, 2012, from Past the measuring stick series, ambrotype on black glass with clear glass face mounting. Courtesy and © the artist.

James Tylor, Deleted scenes (from an untouched landscape) #6, 2013, inkjet print on Hahnemuhle paper, velvet. Courtesy and © the artist.

This feature article published in Artlink Magazine 1st of June 2014.